Under Mao as under Stalin, the will to shape music so as to convey ideologies and appeal to the masses was a central issue. The creation of such a new aesthetic required the implementation of bans on previous forms of music such as traditional music and classical Western music in China or religious music in USSR for instance, but also required the creation of institutions that would define this new aesthetic under the leadership of major figures such as Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife in China, and lastly called for the close management of artists and music creators and their « rectification ».

An historical approach to music aesthetic under Mao

In her study « The politics of the Modern Chinese Orchestra: Making Music in Mao’s China, 1949-1976 », Ming-Yen Lee provides us with an historical approach on the evolution of the creation of a new music aesthetic in China through studying the Chinese orchestra.

Ming-Yen Lee identifies three period that presented nuances in terms of musical creation in China: the first period from the founding of the PRC to the dawn of the Cultural revolution (1949-1966), the second period from the early beginnings of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1971) and the last period concerning the last part of the Cultural Revolution (1971-1976). Studying more closely those period of music creation allows us to identify the progressive construction of new music aesthetics in order to build and convey ideologies as well as a cult of personality.

Mao was highly concerned about music creation as he deeply believed that music was a « bridge of communication » between the leaders of the CCP and the people. Therefore, Mao’s pronounced two important discourses that would have a huge influence on the shaping of music under its rule, first in 1942 with its « Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art » and then in 1956 with its « Talks to Music Workers ».

In his 1942 speech, Mao’s underlined the fact that music should reflect the idea of the Communist party but should also be understandable by a large audience, having in this respect a similarity with what was aimed under Stalin, this idea of appealing to the masses as we will discuss later in this article. Mao’s even encouraged music creators to read Marxist and Leninist works.

But concerning this idea of shaping a music aesthetic, the 1956 « Talks to Music Workers » is quite unbelievable having in mind the communist thoughts. Mao’s exhorts the music workers to study Western music in order to learn from it saying « The ordering and development of Chinese music must depend on you who study Western-style music, just as the ordering and development of Chinese medicine depends on Western-style doctors. » This aspect must be underlined as it shows that Chinese music may have been influenced by Western music in this era.

Later in the early 1960s, Mao called for the « Two instructions » led to the creation of the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra in 1952 and the China Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra in 1953, and other conservatories were created. Those institutions handed over to their students the new aesthetic that had been decided and implemented.

From 1966 to 1971, in the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, the message was quite clear, Mao wanted music workers capable of “using ancient material in a modern way, and the Western style in a Chinese way”. This period also witnessed the increasing influence of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, that eventually led to the creation of the Revolutionary Operas, that will be discussed later in this article.

Lastly, in the second half of the Cultural Revolution, more freedom was given to music creators reflecting the international context of the Sino-US rapprochement.

During all this period, Chinese composers took the Soviet Union as a key source of inspiration as the exchanges between the two communist countries were, until 1958, numerous, notably concerning revolutionary songs reflecting socialist ideals.

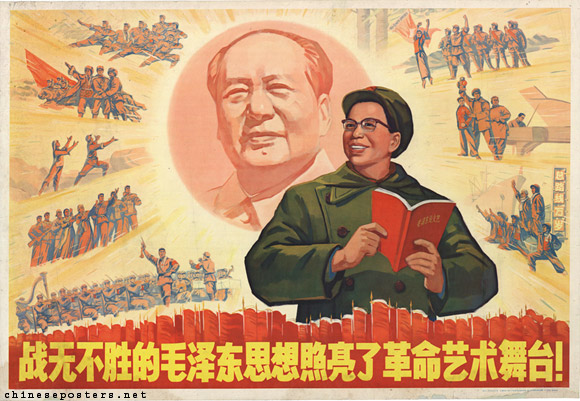

Chinese Revolutionary Operas: a new aesthetic under the impulsion of Jiang Qing

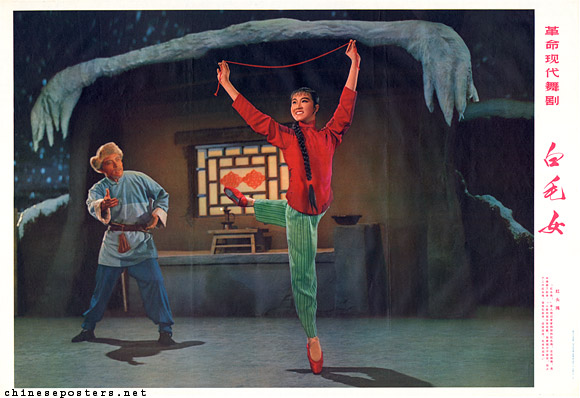

The Chinese Revolutionary Operas are at the core of the idea of shaping a new cultural aesthetic in order to convey ideologies. They were created in the context of the cultural revolution under the supervision of Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife, whose influence during the cultural revolution was at its height.

Those operas represented the revolutionary struggle of the People’s Liberation Army against the class enemies. The idea of those operas was to glorify the People’s Liberation Army involvement as well as to show the predominance of the figure of Mao in winning against the enemy. Thus, this particular form of music was used for political ends in order to convey ideologies and a cult of personality. During the Cultural Revolution, those operas were part of a larger music creation with eight pieces of music (five operas, two ballets and one symphony).

Those operas were not intended to only be played in concert halls, opera houses, or conservatories but were rather played at schools and factories for instance and quickly became part of the daily life of the Chinese citizens under Mao. The testimony of Anchee Min is quite revealing about this idea of using music in order to convey ideology, with similar characteristics as the world described in 1984. Min says: « I listened to the operas when I ate, walked and slept. (…) I could not go on a day without listening to the operas. » Those operas were then essential as they were powerful soft propaganda tools at the service of the CPP leader and illustrates this idea of shaping a new music aesthetic to produce music for political ends. It also illustrates the idea of creating music for the masses.

Appealing to the masses

The idea of appealing to the masses was common under Mao and Stalin. Mao believed that artistic activities will be efficient soft ways of conveying his ideology to the masses. This idea is one of the pillar of Mao’s speech in 1942 at the Yan’an Forum where he insists on the fact that music workers should make music taking into account the audience they were targeting, i.e. the people. This aspect of music was also particularly important for Stalin in his attempt to implement Socialist Realism in music. Dmitri Shostakovich 4th symphony was eventually withdrawn by the regime waiting Shostakovich for writing a symphony that would be understandable by the large Russian audience, a desire that would then be materialized by the 5th symphony. This last idea underlines the somewhat contentious relation that existed during Stalin and Mao’s rule.

Music creators and the regime: a contentious relation

As the music creators – or « music workers » as they were called in PRC – were the main tool for creating music and thus to convey ideology in a subtle and soft way, they were seen as yielding a huge responsibility. This was underlined by the idea of giving orientations to music workers, but also through conflictual relations and lastly by the highlighting of soloists by the regimes.

To begin with, the regime closely organized the way music was created. Andrei Zhdanov, appointed by Stalin, castigated all the composers that were not conforming to the regime orders, i.e. incorporating revolutionaries and nationalists themes in their music. Under Mao, the same was true when in the late 1963, Mao criticized the lack of realization of socialist ideals in artistic creation, criticizing the artists that had, in his opinion, « inappropriate » behavior. This was followed by the odd « self-rectification » of art associations admitting their faults. Jiang Qing played an important role in this respect, by pushing Mao to set new institutions in June 1964 that would have to deal with artists who failed to « produce works that reflected the socialist revolution ». Tensions were strong among artists, some of them being marginalized under what was called Mao’s period of the « Two Instructions ».

Nevertheless, the relationship between the regime and its musicians was not always so conflictual. Stalin had set up his own prize, the Stalin’s Prize that notably rewarded Sviatoslav Richter who was put into the limelight by the regime and quickly made concert tours in Russia, Eastern Europe and China. Ying Shengzong, is an other example of a pianist that played a role in conveying the ideology of the regime by adapting to his instrument one of the eight model plays, The Legend of the Red Lantern.

To put it in a nutshell, from Mao to Stalin, the creation of a new aesthetic by implementing new institutions and giving orientations to the music workers, was central and at the basis of conveying ideologies and the cult of personality.